|

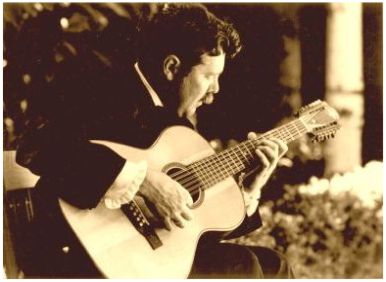

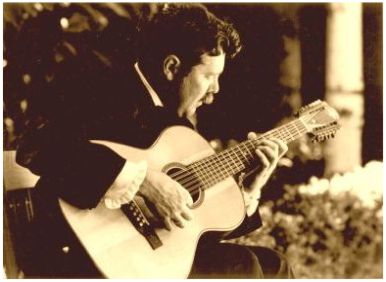

ROBBIE BASHO - ARCHIVES |

|

Home

| News

| Biography

| Discography

| Visions

| Style

| Special/Live

| Shrine

| contact/imprint

| disclaimer

| | DEUTSCH |

Recollections

About Robbie BashoA personal story about Robbie Basho in the early '80s: "In the early 80's I was browsing at Leopold Records in Berkeley. A man entered, announced himself as Robbie Basho at the counter and inquired about buying some of his old L.P.s The sad implications of this request impelled me to withdraw from earshot...." Dorian's Writing and Photo Journal But in addition to this personal story, we have to say something about the background: Actually the implications of Robbie buying his own old lps were not sad at all; just an example of Robbie's good business acumen: Whenever he wanted to play somewhere he would send large stack of used copies of his albums to give away for possible reviews, and for the possibility to give to business owners and schools a representation of his music. Also, at the gigs he always brought boxes including used copies of his old lps to sell at his concerts. THE LIFE AND TIMES OF ROBBIE BASHOED Denson's notes to "The Seal of the Blue Lotus" by Robbie Basho (1965 - Takoma, reissued 1997 by Fantasy):It is difficult to write a biography of a contemporary musician, even a sketch like this. When dealing with an old blues singer certain things seem significant and information is sparse enough to allow a main trend to be discerned which will include almost all of the information available. By contrast, having lived through most of the events of Robbie's life I have on the one hand much detailed knowledge and the other, certain blind spots. At the center of my knowledge is a blank - - the mystery of the causes of events and trends. Robbie was born on August 30, 1940 in Baltimore. I know nothing of his childhood, and doubt that it has any bearing upon his adult life, Freud notwithstanding. In the summer after his junior year at the University of Maryland, he was working in Ocean City, Maryland to earn the money for his final year of college and presumably his entrance into suburbia. In his spare time he lifted weights, a practice which probably helped give him the vitality to survive the years to come. One evening he met a sailor who had just returned from Mexico, bringing with him a 12 string (nylon) guitar upon which he hoped to play flamenco. Quite naturally flamenco and the 12 string do not mix, so the sailor sorrowfully allowed Robbie to buy the instrument for $200. Earlier in the season Robbie had owned a $10 guitar, which he had screwed around with, but it had been destroyed accidentally. Now he borrowed the money necessary and cheerfully traded the good time living in College Park for the beauties of his art. It is from this time that he dates his serious interest in music. Give an untutored person a guitar and an interest in playing it and no particular prejudices and at that moment a high of existential freedom appears never again to be equaled in his career. Classical music, bluegrass, oriental, improvisations on Bing Crosby -- the entire universe is potential. From that instant his musical future is created largely by his environment, the possible models it offers, and the limitations imposed by the ignorance and bigotry of the existing musicians. Robbie returned to the University of Maryland, rented a basement, began painting, writing poetry, and playing the guitar. Within a few months he was to enter the musical scene of Washington just as it flourished. It was the most vital and creative center of folk music in the country. If there are any two things that are necessary for a modern folk scene they are an established beatnik community and performed of some ability. In the late 1950's Washington had both despite the hostility and disdain which the pioneering families of both settlements felt towards each other, the younger generation, restless in suburbia, was pouring onto the scene to rustle the sacred cattle of each faction and combine the herds. The beatniks had appeared on the scene in the wake of Kerouac's success On the Road. Opening Coffee and Confusion the DC school of beat began making a fortune by swearing at the audiences which often stood in a double line a block long for the privilege. Liberated by the thaw in the suburbs, where a few years earlier parents in the suburbs seemed on the verge of forbidding their children to smoke certain brands of cigarette lest McCarthy discover the true meaning of the red package, a generation now discovered the strange men with beards and earrings, We flocked down like lemmings, to mix with the local Negroes who had made the equally momentous discovery that putting on shades and staying out at night they were transubstantiated from niggers into artists. Equally exciting but contrastingly pure and American were the hoots John Dildine was holding at the park service facilities and the Jewish Community Center. It was possible to hear in one evening, the two local hillbilly groups, the New Lost City Ramblers and the Country Gentlemen, and then perhaps Fahey playing an unheard of blues. The lets-keep-American-folk-muisc-off-the-streets-and-in-the-parlour forces were in their heyday and although badly set back by the coming bohemian infiltration they regrouped in time to help destroy the scene and still wield considerable power in the current Washington Renaissance. The beatfolk first got together in the Unicorn, a new coffee shop opened when bohemia grew enough to seem to a allow a subsistence existence to two establishments. For the first period of its existence it was one of the few true coffee houses to exist in this country. Open in the daytime it stocked newspapers and magazines and kept a chess board for its patrons. Far from having a door charge, the proprietor understood that many of his customers were unable to even to buy coffee, and welcomed them all. Such places must draw money somehow and by the early 1960's poetry was about as money making as the heroin concession on an LSD farm. Taking an idea from the Java Jungle, another coffee house whose temporal location in this foggy chronicle is uncertain although I still recall dim as evening seeing the Fausts, Jeff Glaser and Larry Fagin all on the stage at once amidst a heap of autoharps, guitar and banjos, the Unicorn began having folk music nights. An Awareness of these events slowly penetrated to the College Park Campus. The normal routine of a second-rate university is unbelievably stultifying: my roommate, popular in our dorm, rose at 6 a.m., stared at the plastic Jesus he had hung on the wall, and went to the gym to work on his thesis - - a history of the Business and Public Administration building on the campus. Every swamp has its dry spots, and every creature that doesn't wish to drown live on them. The dry spot in our mud was the creative writing classes given by Rudd Fleming, and Robbie, now a poet, started taking them. There he met Max Ochs who introduced him to folk music, took him to Jefferson Crafts in Annapolis where preparations were being made for the Blind Willie Johnson reissue that was to have started a luminous career for Silverleaf Records. Although Jesse Fuller's record held the spot of honor on the altar of creative music there, already tapes from the fabulous Spottswood collection were beginning to displace him. Personality conflicts between Serge, the Jazz drummer, and Robbie dictated that the influence of Jefferson Crafts should be less than the delights of another center of culture that Max showed him - - the University of Maryland library. Under the influence of Richard Spottswood who worked in the music department they had accumulated a dozen of the best that Folkways had to offer and the Lomax series on Atlantic. In the brief months between acquisition and the time the music was hip enough to be stolen from the shelves, those records were, in conjunction with the tapes that Dick was sending out to infect us all with appreciation for the blues, of incredible consequence. They catalyzed something in many of us from Fahey and myself to Ochs and Basho and countless budding hippies from the dorms. Robbie began playing blues, and a mixture of foreign protest songs which were our legacy from the New York strumming school. It was that exciting time when in a few days everything clicks, you quit the fraternity and when you come down you are downtown in someone's pad with thousands of ill-formed ideas spinning your eyes. By the time rapture of the depths has worn off after a dive into bohemia you are on the shores of an uncharted island with no idea how to return. Robbie woke up at the Spider Lady's and found himself playing at the Unicorn. Wings of innocence and mysticism let him float happy as a duck at Dunkirk in those days of gunfights, insane parties and destroyed apartments. The last apostle of the New York folk song, Dave Tucker, was the star of the house, thrashing on the guitar and yelling songs of Nagasaki and mining disasters, but already the new folks were emerging in the person of Bill Roberts, whose harmonica technique had been learned in New Orleans and whose version of "Keep on Truckin' Mama" raised something more potent even than social protest in the breasts of the chicks. Even French bedroom songs with English translations coyly given between verses fell before him. Each school of thought had won supporters, but they all appeared on the same stage, and Robbie's music became a composite, accompanied by his operatic voice. Any scene is made up of numerous rapidly shifting cliques, each intolerant of most of the others, and the only way to make use of the best that is being thought is to be a leader and consequently comfortable enough to be open minded, or either and outsider and consequently too uncomfortable with any group to fully adopt its dogma. Robbie was the latter, always too much on his own trip to fit. Despite the American dream of individualism, few are isolated by choice, even though it is often best for them. Certainly Robbie wasn't, but the fortunate accident of his distance gave him the objectivity, and the desire to be part of the scene gave him the interest necessary to select the part of the music going down which was of the most value to him. His life then was made up of the most diverse experiences. One evening he taught Lisa Kindred the words to "Hard Time Killing Floor Blues", which he had learned from Backwards Sam Firk's tape of Pat Sullivan singing Skip James' song; another day he and Max Ochs were invited, by a whimsical hindu, to lunch at the Indian embassy after which they entertained the staff with a concert. Robbie met Fahey after hearing his record at the Spider Lady's and getting her to introduce them. Fahey invited him to the final rehearsal for the Episcopal Youth Show, and one thing led to another until Robbie found himself on the stage in a church playing second guitar while an unsuspecting girl read from the script Fahey had written: "The next song was sung by an old Cajun woman discovered by Samuel B. Charters in Watertight, La. No one could understand her dialect and unfortunately she died the next day before a translator could be found, but the melody survives", and then the ensemble played a Fahey invention, followed by a guitar and kazoo version of an old Columbia record with the church organist, who amused himself by playing Alte Blau (Handel) during meditation periods, taking lead kazoo. The study of folk music is full of surprises, as Amborse Bierce said when he rediscovered the band of Pancho Villa. Doubtless the drastic changes Robbie's music underwent when he left DC had its roots in this period. Enough things like this and your head becomes twisted. Although for a time the Washington scene was flashing like Einstein on amphetamine inevitably it began to come down. The parlor boys got an unexpected ally when the Unicorn changed hands. The new owner decided to attract the embassy crowd. He effected his enticement by banning beards, Levi's and dope from the premises. Quite naturally the embassies now free to hear American folk music unhampered by disreputable elements, stopped. The Unicorn folded in a few months to the immense joy of certain elements, but with it went the remnants of the scene. Before it died, however, it managed to be the stage of one last happening to Robbie. Baez came to town, and undoubtedly not realizing the truth, went to the Unicorn to sing a couple of song. Thus many of our artists are duped by seemingly shaggy people into supporting suburban values. Robbie sang with her and she gave him a rose which he kept in a beer can on the Spider Lady's mantle, until seeing it begin to wilt, and after several frantic phone calls found no firm willing to plastic coat it, an ill advised attempt to preserve it in molten wax taught the young novice of the transience of earthly beauty. As the DC scene folded, one by one we fled, quite naturally mostly to Berkeley. Robbie, who has great staying power, was there until the very end. He caught a ride to Denver where he renewed his acquaintance with a dominant force in American life. Being offered a place to stay the night in the as yet uninhabited home of a local merchant, Robbie was awakened by a kick to be beaten by five cops who had gotten a complaint that "some weird guy was sleeping here." He played the Green Spider got two weeks getting enough money to make the coast. Arriving in Berkeley ragged and dirty, broke and hungry too, his life was saved by eating raspberries from the patch by Fahey's house. A brief gig at the Jabberwock and Robbie moved to Sausalito, recently in the news for making it illegal to play the guitar in public, and got a place on the houseboat Carles Van Damn. He began developing his hindu music there, but was "run off by a madman" and ended up playing several now extinct coffee houses in Portland. From there he went to Seattle where he studied Yoga and performed at the Queequeg. Through the kindness of Jeremy Lansmann he was able to record a number of pieces at KRAB, several of which are included in this album. The radical nature of the new direction taken in the months after he left Washington is evident in the commentary on the songs: MOUNTAIN MAN'S FAREWELL: Sometime I feel the flavor of Cosmic Essences: the hue of nature colours; Moods given to the airs of music. In this piece and several others I enter what I call the Theater of North American Taoism. This continent is new, the rocks are raw, the winds are sharp, the heart is rash and wild. The Taoistic Essences of China and Japan are aged with the mildness of human culture. Ours, being new bits like the persimmon to be aged to the taste of the Universe. Standing on Lone Dark Mountain, overlooking all of North America, the raw echo of the Eagle Man, onto Bowel Mountain man, the Soul Heart of the men red and white who made the Mountain Man Ear, an Epic Picture whose bloodstain is carried up to a Present if many soul-brothers. An echo of farewell and away into past Karma. The Snowstorm technique, an innovation of mine is here used at its fullest. DRAVIDIAN SUNDAY: Dravidian is an ancient race in India. The theme is poured out with Hindu flesh paints. Elephants of a Golden Age in Hindu history. From this beginning the piece is developed from that time era to the present North American continent and its sounds, exploring and remembering, cliaxing and returning to where the clouds move away and the birds chirp at the break of day so old and yet so young. SANSARA IN SWEETNESS AFTER SANDSTORM: "It is done in D minor modal (Frog minor). Flowing naked into beauty getting clobbered by a sandstorm and flowing out again." The commentary to another piece, the Rainbow Raga, which space would not permit us to include in the record also casts light on Robbie's ideas: It dips into a theory I have concerning sound and colour. Every chord has a colour, every section of that chord a shade, every note a drop. Chords may change colour by Velocity. Mood is coloured air. The piece explores a span of three mood formations: a) Runnymeade, England - - Green b) St. Louis - - orange and blue c) A hindu pourri of gold and purple thruout. Anyone who follows the intellectual ideas among the bohemian folk community is aware of the widespread acceptance of various exotic offshoots of 16th century Neo-platonism and corresponding oriental analogs. From witchcraft to prophecy, Zen and the LSD cults, these ideas have a currency that makes the dabbling of T. S. Eliot and W. B. Yeats conservative, particularly on the West Coast. The unorganized nature of the believers coupled with the general feeling that it is a drag to be a fanatic have resulted in a great eclecticism. No dogma has arisen in any strength connected with these thoughts, and it is very difficult for people to communicate on a specific level because the vocabulary is very arbitrary and vague. Consequently most individuals do not realize the ramifications of their beliefs or their relationship to other ideas and they will often reject a premise and while embracing the conclusion. So, it is infrequent that the ideas are combined in such a coherent and daring synthesis as Robbie's where each object has a homolog, a color, and sound. To those interested in gaining full comprehension I would recommend a passive approach, intensive music allowing the aura to infiltrate the consciousness rather than attempting an intellectual assault. A chart giving the properties of various chords and tunings will be found at the end of the notes. These tapes were sent to Folkways for an audition, but before an answer could be received , police harassment forced Robbie to leave for Canada. There he played the Bunkhouse in Vancouver and the Secret in Victoria. At the Calgary Rodeo he met Bruce Langhorn and under his influence composed the BARDO BLUES An attempt at a musical rendering of the Tibetan Book of the Dead - - Bardo Thodol. It moves thru the beginning of death, subsequent limbo voyages, into rebirth. The voyage moves geographically from Africa to the Roof of the World, Tibet. The Style is that of my old wandering. For the initial technique I am indebted to the master guitarist - - Bruce Langhorn. It was recorded live at the Bohemian Embassy in Toronto, by Wall Parsons. Takoma apologizes for the quality of this recording but the piece was un-duplicable and we are thankful that any record at all was available. From Toronto, Robbie took a bus to New York and spent three days and nights, sleepless, looking for a place to stay. Finally, he was rescued by a fraction of French painters who traded him bed for board. Robbie worked the basket houses in the village until he was fired for being non-commercial. At the same time he fell in with Allain Ribback who was working with paramusic. A short and perhaps unjust description of the idea behind the music is: a group of nonprofessional musicians intensively play together until they achieve a music which is expressive of the group as a whole. Robbie did some work with Allain and the Black Lotus - Hymn to Fugen was recorded during this period. A blackwash painting of tonalities in the realm of the Black Lotus. I am aided by wooden organ drums and temple-bells. I am also very indebted to Allain Ribback on drone guitar. He made these pieces possible. Fugen is the goddess of the Lotus Sutra, of Charity, of Gentleness. This is a hymn of deep spiritual passion rising and falling and finally rolling on the carpet of the clear with the aid of Sweet Bikshu Bells. The financial assistance gotten from Ribback kept Robbie alive for two weeks and enabled him to return to the West Coast. Arriving in Berkeley he went to KPFA, a non-commercial radio station in Berkeley, and told them he was doing hindu-textured music. There he met a hindu dancer, Ishvani, for whom he composed several pieces. This record was begun at the same time. The easy going relaxed way we have of recording permitted him to go to Seattle for a few weeks during which time he located a group of Tibetan Llamas who were translating documents smuggled from Tibet. Robbie did extensive library research on their culture and iconography and attended several lectures, given in Tibetan, so that he might "puncture the psychic texture or mood of Tibet." On his return to Berkeley he recorded THE SEAL OF THE BLUE LOTUS. The basic texture for this piece was taken from Ravi Shankar's "Dhun in Musra Mund", a raga invoking the Religious Springrasa Mood in Hindu Aesthetics. With this base I inject the Taoistic Taint of the Blue Lotus which is a musical realm of my own. The guitar is tuned in the colour blue, which is standard open Open G tuning with the 2nd and 4th strings dropped to a minor. This record was recorded in Seattle at KRAB, in Toronto by Wally Parsons, in New York by Allain Ribback, and in Berkeley. Takoma records and Robbie Basho wish to express their gratitude to those that made it possible. In addition we wish to thank the following persons for their aid and support: Philip Ault, Bernie Cordt, the Jabberwock coffeehouse, Jon Lundberg, Moe Moskowitz, and Timothy Scripts. Produced by R. Basho and ED Denson; mastered at Sierra Sound Laboratories. We wish to thank the Bullfrog Eradication Company for granting Mr. Denson a leave of absence to prepare this record. JOHN FAHEY: in THE WIRE "Blood on the Frets":Takoma had also established a label identity with its distinguished roster of guitarists, capped by the release of up-and-coming guitarist Leo Kottke's classic debut, Six And 12 String Guitar. Fahey smiles, "Everybody in the office said, 'That's no good, it won't sell. He just plays like you do'. I said, 'No he doesn't' But I just saw a big dollar sign on the wall." The roster was completed by Peter Lang and the eccentric Robbie Basho, whose two volume release was called The Falconer's Arm."He was crazy," Fahey laughs, "very hard to get along with. I didn't put out his records, ED Denson did. I never really liked them until Al Wilson pointed out that there were some really good songs. He was right, there is some great stuff on those records. I never hung out with Robbie personally much. Nobody did. You couldn't." Compared with one act that turned up in 1969 looking for a deal, however, Robbie Basho was a model of sanity. NEW YORK CONCERT REVIEW by RAY JOW:someone in front of me on line had four fonotones, and i had previously only seen this on website and through hearsay. I have never seen them and know about its history only through stories and myths. there was one by blind thomas, one which featured robbie basho in a group, and two others i cannot remember. when john saw these, he said, "those are collectible but they're not even good" (repeated twice)...WILLIAM ACKERMAN:I think there is still a lot of influence from Basho, frankly. His very linear way of playing guitar which treats it more like a sarod - the influence of Ali Akbar Khan for the most part - working in an open C. So much of what I learned was inspiration from Robbie Basho. More than any other player, he's the one that I studied. It's true that my approach to how chords are played is more classical than Basho's. He was content to stay in a really raga-esque place in terms of picking. As my music evolved, I found I was doing less in terms of playing melodies exclusively with the thumb on the third, fourth and fifth string as Basho did in imitating the sarod. I was using chordal stuff more, but the movement up and down the neck is still very much a product of Basho.Robbie Basho was an angel. I don't believe he was terrestrial. I would watch him play and be transported in a way I've never been transported before. I'd see him have conversations with people who I did not see in the room. I truly believe that his reality was more accurate than mine. He was seeing a spirit that I was not. I think he may have died a virgin. Robbie didn't have a driver's license. He was not of this world and was not equipped to be part of this world. I'm not surprised he left this world early. It must have been very tiring for him to try to be in it, but his influence on me is so vast and seminal that I can't possibly overemphasize it. I think people should go back and listen to his music. There's some powerful, powerful stuff. Though his voice was odd, it was so powerful. I never really studied with Robbie. I wanted to but I was just too undisciplined to do it and at some point Robbie, exasperated, said to me "Oh, so you need the short lesson." I said "I guess so," and he said "Don't be afraid to feel anything" and "Sing every melody out loud. If all you're doing is guitar riffs, there won't be enough there." Very often a guitarist thinks he's playing a melody when all he's doing is a chordal progression with a picking pattern. Unless you can sing the melody as an independent thing and have it work as a melody just note by note by note, you haven't really written a melody. It's one of the greatest exercises to engage in when writing. It was a tremendous tool that he gave me. He lived on a spiritual plane that was very real and he made beautiful, beautiful music that people would be well served to listen to today. Doing records with this man who I revered was a big deal for me. LEO KOTTKE:He had a big effect on me. He had an old 12-string guitar and used to wear cowboy outfits and carry around Japanese movie review books. He sang a lot more a traditional mode back then, and I always loved his voice -- it was really good, and spooky . I'd keep trying to talk to him, and one night at a place called the Unicorn I was following him and I said, "Gee, I'm really kind of nervous, because I've been listening to you so much, I'm afraid I'm going to sound a lot like you." And he said "Aw, that's all right, we all go through somebody sooner or later.""I just never thought it would be a job but it turned into one" Leo Kottke interview By Tom Murphy Fri., Jan. 27 2012 Who is Furry Jane? That's a good question. The song was Robbie Basho's favorite song of mine and Robbie was a guy who was entirely unknown to himself. And I mean that in the most absolute sense 'cause I met him when I was a kid in high school and I'd follow him around. He was not the guy that...well he remains obscure but he did make a few records on the label I wound up on briefly. He was an entirely different guy when I knew him. He was a cowboy that was into Japanese movies, and he was drunk all the time, and he sang all the time, and he didn't go anywhere near all the stuff that he became later. When I talked to him on the phone and he told me about Furry Jane, I said, "I remember you from high school. Remember me? I used to bug you and drive you crazy asking you questions about your twelve string." He said, "What do you mean?" I said, "When you were playing around DC and Maryland." And he said, "Uh, that wasn't me. I didn't play around there." I said, "Well you were a cowboy, and you were always wearing boots and all that garbage." He said, "No!" "You're into Japanese movies." "No! No, that wasn't me." It was him.(read more..) There are some customer reviews about "Guitar Soli" on Amazon.com. I don't agree with everything written there; Some show, that not everybody can understand Robbie's approach and music. We can't compare his music whith more common guitar standarts; it has to be seen related to the time and to the personal history of a young musician and his ideas and visions. Some of the reviews are interesting and tell something about how listener today can understand Robbie Basho: Richard S. Osborn "artpaws" (Saratoga, CA USA)- friend and colleague of Robbie's said about "The Seal of the Blue Lotus": There are several truly atrocious pieces on this album. But keep in mind that all of the music comes from his earliest recordings. To understand what is going on here, remember Robbie's own guiding axiom: "Vision first, technique second". You are listening to a kind of musical record of one man's inner spiritual journey, someone whose soul expanded with visions from India, Tibet, China, Iran, Armenia. So, to the reviewer who trashed this album, I would say: you have missed a rare glimpse into the creative process itself, what jazz musician's call "deep in the shed", LONG before it gets polished and prettified for public consumption. see more and "chrisjr" (Orlando, FL United States) wrote: Robbie Basho is always lumped in with Leo Kottke and John Fahey since he shared the Takoma label and was an innovative talent himself, however it's not fair to compare Robbie Basho to either aforementioned guitarist. Basho has been referred to as "psychedelic" and "spiritual". His compositions don't draw on the same roots as Kottke or Fahey, and though his raw passionate sound certainly parallels the power of Kottke's plucking and Fahey's experimental out standings, Basho still traverses a land all his own. True, Basho may be an acquired taste especially when one is familiar with the precision of Kottke, as precision wasn't Basho's aim--expression was. Basho had a punk attitude; he was more interested in making the music then making it "technical". In a sense he comes off as more an idealist and romantic than Kottke, and not as spiritually gimmicky, for lack of a better term, as Fahey. Kottke and Fahey aside. Let's look at Basho. This CD represents a good sampling of his earliest recorded work, it's very raw and edgy and when Basho "sings" (in tongues) or whistles it's eerie but beautiful. Basho's later works are more accomplished in the traditional guitarist sense, but to me less interesting and less obviously innovative than his first few recordings. Basho is endlessly experimental and endlessly expressive. You'll here subtle ambient sounds behind his guitar like bells and chimes. It sounds authentic; one can imagine sitting on a monastery porch next to the guitarist in some far away Eastern land. see more

|

|

Home

| News

| Biography

| Discography

| Visions

| Style

| Special/Live

| Shrine

| contact/imprint

| disclaimer

| | DEUTSCH |

| www.robbiebasho-archives.info © 2021, Robbie Basho Archives Berlin (Germany) | info@robbiebasho-archives.info |

|